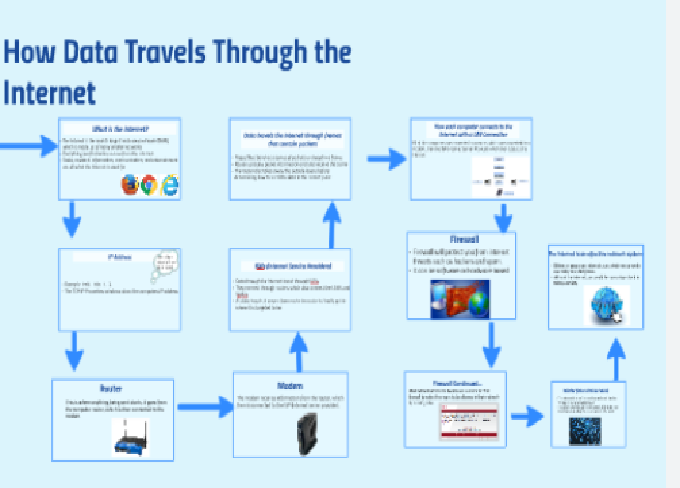

The internet might seem like magic — you type a website name or send a message, and within seconds, it appears on someone else’s screen halfway across the world. But behind this apparent simplicity lies a fascinating, complex process. Every text, image, video, or file you send travels through multiple layers of hardware and software systems.

In this article, we’ll explore step-by-step how data travels across the internet, breaking down the entire journey — from your device to the destination server — and back again.

1. Understanding What “Data” Means on the Internet

Before diving into the journey, it’s essential to understand what “data” actually is.

On the internet, all information — whether it’s a YouTube video, an email, or a Google search — is converted into binary code (a series of 1s and 0s). These 1s and 0s are grouped into packets, small chunks of data that can be sent and received independently.

Each packet contains:

-

Payload (the actual data, like part of an image or a paragraph of text)

-

Header (information about the sender, receiver, and order of the packet)

-

Error-checking information (to detect any transmission issues)

So, instead of sending one giant file, the internet breaks data into smaller packets that travel through multiple routes and are reassembled at the destination.

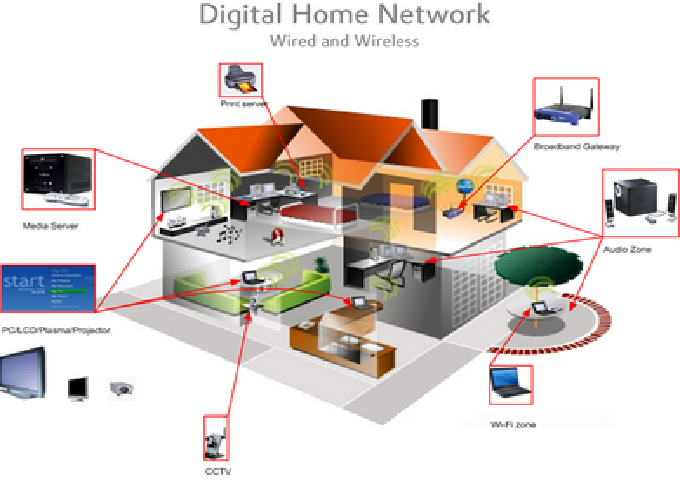

2. The Role of Devices and Network Interfaces

Your journey on the internet starts with a device — a computer, smartphone, or tablet. This device connects to the internet using a Network Interface Card (NIC), either through a wired Ethernet connection or wireless Wi-Fi.

When you request a webpage (say, typing www.example.com), your device prepares a data request and sends it to your local network. This local network could be:

-

Your home router, connected to your Internet Service Provider (ISP)

-

A mobile tower, if you’re using cellular data

-

A public Wi-Fi hotspot, if you’re connected in a café or airport

The NIC ensures that data packets are formatted properly and compatible with the next hop on the network.

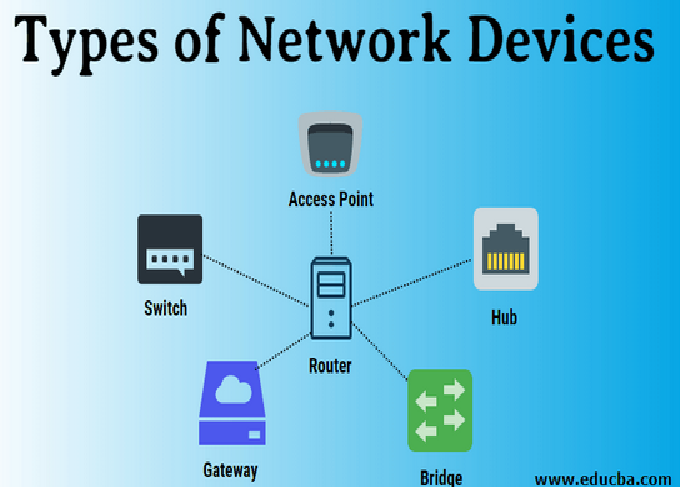

3. The Router: The Internet’s Traffic Manager

Once data leaves your device, it reaches your router. The router acts like a traffic director, determining where the data should go next. It uses IP addresses to identify the source and destination.

For example:

-

Your device might have a local IP address like 192.168.1.10

-

The destination server might have a public IP like 142.250.190.78 (used by Google)

The router checks its routing table, which tells it which direction (or interface) to send the packet toward the destination. If it doesn’t know, it forwards the data to a gateway, usually managed by your Internet Service Provider.

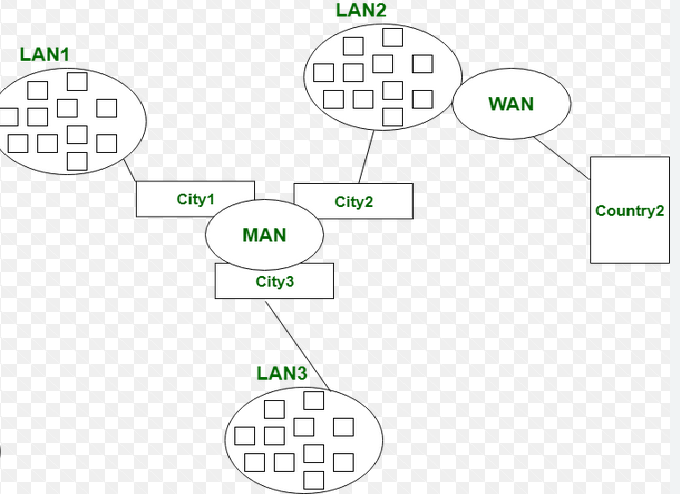

4. Internet Service Provider (ISP) as the Next Hop

Your ISP is the bridge between your local network and the global internet.

When data reaches the ISP, it travels through their network infrastructure, which consists of:

-

Fiber optic cables

-

Network switches

-

Data centers

-

Backbone connections to other ISPs

The ISP assigns your connection a public IP address — this is the identity your device uses on the internet.

From here, your data packets are sent through multiple hops across the ISP’s routers and then out to the global internet backbone — the high-capacity network that connects countries and continents.

5. Domain Name System (DNS): Translating Names into IP Addresses

Humans use names (like facebook.com), but computers and routers use numerical IP addresses. The Domain Name System (DNS) acts as the internet’s “phonebook,” converting website names into IP addresses.

Here’s how DNS works step-by-step:

-

You type www.example.com into your browser.

-

Your device checks its cache to see if it already knows the IP address.

-

If not, it asks a DNS resolver (usually operated by your ISP or a third-party service like Google DNS).

-

The resolver contacts other DNS servers (root, TLD, and authoritative servers) to find the correct IP address.

-

The resolver returns the IP address to your device.

Now your computer knows where to send the request — the web server’s exact address.

6. The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP)

At this point, your device has the destination IP. It now needs a reliable way to send and receive data. That’s where TCP/IP comes in — the fundamental communication framework of the internet.

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol)

TCP ensures data reliability. It:

-

Breaks data into packets

-

Numbers them for proper sequence

-

Confirms receipt of packets

-

Resends any lost or damaged packets

IP (Internet Protocol)

IP focuses on delivery. It defines how data packets are addressed and routed between source and destination devices.

Together, TCP/IP guarantees that your data travels safely and in order — no matter how many routers or networks it passes through.

7. Data Packets Enter the Internet Backbone

Now your packets are ready to travel through the internet backbone — a vast network of high-speed fiber optic cables connecting ISPs, data centers, and major internet hubs around the world.

These cables are owned by large telecom companies and organizations. They span countries and even run under oceans, known as submarine cables.

As your data travels:

-

Each router along the way examines the packet’s destination IP

-

It decides the next best route based on network traffic, distance, and availability

-

The packet moves from one network to another — a process called routing

This journey may involve dozens of routers across multiple cities or even continents, but each hop happens in milliseconds.

8. Network Layers: The OSI Model Explained

To understand how all these systems work together, let’s look at the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model — a conceptual framework that describes seven layers of communication.

Layer 1: Physical Layer

Involves the actual hardware — cables, signals, modems, fiber optics, and network cards.

Layer 2: Data Link Layer

Handles data transfer between devices on the same network using MAC addresses.

Layer 3: Network Layer

Routes data between different networks using IP addresses.

Layer 4: Transport Layer

Manages reliability and data flow (TCP or UDP).

Layer 5: Session Layer

Maintains sessions (for example, staying logged into a website).

Layer 6: Presentation Layer

Translates data formats, encryption, and compression.

Layer 7: Application Layer

Where user-facing applications like browsers, email, or games operate.

Each layer interacts only with its neighboring layers, making data communication modular and standardized.

9. The Destination Server Receives the Data

After traveling across the global network, the packets finally reach the destination server — for instance, Google’s web server if you’re visiting google.com.

Here’s what happens next:

-

The server’s firewall checks the packet for security.

-

If approved, the packet passes to the server’s network interface.

-

The TCP layer reassembles the packets into the original request.

-

The web server software (like Apache or Nginx) processes the request.

The server now prepares a response — typically a webpage — and sends it back to your device, following the same path in reverse (though not necessarily through the same routers).

10. How Data Returns to Your Device

When the server sends data back to you, the same principles apply:

-

The information is broken into packets.

-

Each packet is labeled with your public IP address.

-

The packets travel through multiple routers and networks.

-

Your router receives them and sends them to your local device.

Your device’s TCP/IP stack then reassembles the packets in the correct order, checks for errors, and delivers the data to the application (like your browser). Finally, you see the webpage on your screen.

11. How Routing and Switching Work Together

Two key processes make internet communication possible: switching and routing.

Switching

Takes place within local networks. Switches connect multiple devices (computers, printers, etc.) and forward data only to the device it’s meant for. They use MAC addresses for this purpose.

Routing

Happens between networks. Routers connect entire networks and decide the best path for data packets using IP addresses and routing algorithms.

Together, these processes ensure that every piece of data finds the fastest, most efficient path from sender to receiver.

12. The Role of Protocols and Ports

Every service or application on the internet uses specific protocols and port numbers to communicate.

Common examples include:

-

HTTP/HTTPS (Ports 80 & 443) – for websites

-

FTP (Port 21) – for file transfers

-

SMTP/IMAP/POP3 (Ports 25, 143, 110) – for emails

-

DNS (Port 53) – for domain lookups

These port numbers help devices and servers understand what kind of data they are dealing with and which application should handle it.

13. Security Along the Way: Encryption and Firewalls

Security is a crucial part of data transmission. Without it, sensitive information like passwords and financial details would be vulnerable to interception.

Encryption

Most modern websites use HTTPS, which encrypts data using SSL/TLS protocols. This ensures that even if someone intercepts your packets, they can’t read the contents.

Firewalls

Firewalls monitor network traffic and block suspicious packets. They can be hardware-based (in routers or servers) or software-based (on your computer).

Together, encryption and firewalls protect your data from hackers, malware, and unauthorized access during transmission.

14. The Role of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs)

When you access a global website like YouTube or Netflix, you’re not always connecting to a server on the other side of the world.

Instead, your request is often routed to a Content Delivery Network (CDN) — a system of distributed servers that cache content closer to users.

For example:

-

If you’re in Pakistan, a CDN server in Lahore or Karachi might deliver your video.

-

This reduces latency, speeds up loading, and reduces congestion on global networks.

CDNs are a vital part of the modern internet, ensuring faster and more reliable access to data.

15. How Data Travels Under the Sea

A fascinating part of the internet’s infrastructure lies under the ocean. Submarine cables, thousands of miles long, connect continents and enable global communication.

These cables:

-

Are made of fiber optics that transmit data as light pulses.

-

Can carry terabits of data per second.

-

Are owned and maintained by telecom companies and tech giants like Google, Meta, and Amazon.

Whenever you access an international website, it’s likely that your data has traveled through one or more of these cables.

16. Latency, Bandwidth, and Speed

Several factors influence how fast data travels:

-

Latency: The delay between sending and receiving data. It depends on physical distance and the number of hops.

-

Bandwidth: The maximum amount of data that can travel through a connection at once.

-

Congestion: Heavy internet traffic can slow down transmission.

-

Server Load: The performance of the destination server also affects speed.

Even though data moves at nearly the speed of light through fiber optics, routing and processing delays still cause noticeable lag in some cases.

17. Error Detection and Correction

Data transmission isn’t always perfect — interference, congestion, or hardware issues can cause errors. To counter this, the internet uses error detection and correction mechanisms.

Every packet contains a checksum value — a calculated number representing its contents.

When a packet arrives, the receiver recalculates the checksum:

-

If the numbers match, the packet is accepted.

-

If not, the receiver requests retransmission.

This ensures data integrity, even over long and complex routes.

18. The Final Assembly: From Packets to Pages

Once all packets reach your device, the TCP layer puts them in order, fills in any missing data, and hands them to the application layer.

For a webpage:

-

The browser receives HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and image files.

-

It processes the HTML structure.

-

Loads the styles and scripts.

-

Displays the final visual page on your screen.

All this happens in milliseconds — giving you the illusion of instant access.

19. What Happens If a Packet Gets Lost?

Not all packets reach their destination successfully. Some get dropped due to network congestion or hardware issues.

When this happens:

-

TCP detects missing packets (using sequence numbers).

-

It requests the sender to retransmit the lost packets.

-

The process continues until all packets arrive safely.

This is why downloads resume from where they stopped instead of restarting from zero.

20. The Future of Data Transmission

As internet demand grows, technology is evolving rapidly:

-

5G networks are reducing latency to microseconds.

-

Fiber optics are becoming faster with improved materials.

-

Quantum networking and satellite internet (like Starlink) are pushing data transmission beyond traditional boundaries.

The goal is simple: to make data travel faster, safer, and more reliably across any distance.

Conclusion

Every time you open a website, send an email, or stream a video, billions of data packets are moving across the world in a carefully coordinated dance. From your device to your router, through ISPs, submarine cables, data centers, and back again — the journey happens in fractions of a second.

Understanding how data travels across the internet helps you appreciate the incredible engineering that connects the world and makes modern life possible.